A pair of CF7s toil away on The Palmetto Spur, a layout designed for acquiring the most crucial asset we need to embark on a model railroad layout: basic skills.

Going back in time and getting a redo on some of our past life decisions, the thought crosses all of our minds. Unfortunately, the harsh reality is you can’t. You have to live with the consequences of those decisions, hence the topic of today’s post.

We’d all like to think that we are unique in our life circumstances. Surprisingly, less so than we think. We have a lot more company, more folks in the same boat than we realize.

There’s a pattern I see over and over, among modeling enthusiasts. It’s a series of subtle decisions made over decades. They are inconsequential in the short term. That makes them all the more dangerous because, added up over time, they are consequential in the long term. There is no recovery. There’s no recovery because you simply can’t go back in time and get that redo. It’s the decision not to do anything. You can’t recover those lost decades.

Here’s what happens. You have a smart individual, professionally successful, professionally driven, and extremely knowledgeable about all aspects of railroading. Career and life being what they are, this individual puts off building anything until “some day”, usually retirement.

Someday does arrive. Time is now available, as are ample financial resources, and a nice home. As it turns out, these guys were sincere all along. They are now ready to start that dream layout. They begin the planning process. They have everything they need….finally….right? Nope.

They don’t have the skills to build it, not even the most rudimentary ones. Of more importance, and more subtle, they don’t know what they don’t know. They don’t have a gut understanding of how much work is involved in building X square feet of layout. It’s often much, much than they realize. They don’t have a gut understanding of how many square feet it takes to make them happy (often much less than they think). Because of this benign ignorance, they often assume they need a multi-deck monstrosity to spin off the level of satisfaction they’ve been dreaming about for decades. Without the requisite skills, however, this never ends well.

Then it hits them, and hits them hard, the “Holy shit, I’m screwed” epiphany. True, you can start the skills-building process at retirement, but you’ve lost decades, and you’re at the bottom of the mountain.

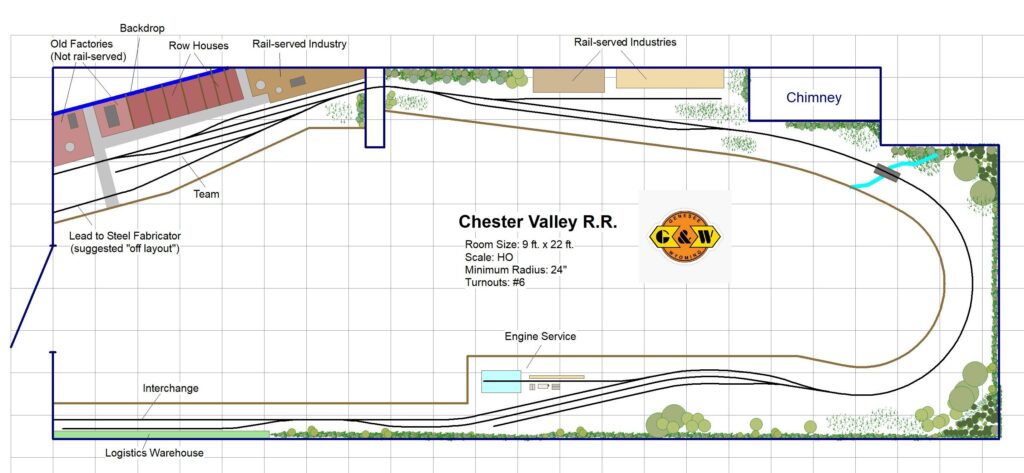

Sadly, this mess could’ve been avoided simply by seeing into the future and planning for it. Sure, many people are truly swamped with life. I get it. However, every person has time to build at least a simple one turnout plank, throw it on the wall, and use it for one reason, and one reason only, to build the basic skills. To gain a gut understanding of the relationship between how much layout spins off how much enjoyment, how much work is involved in building and maintaining an X size layout. (Still short on time? Reduce screen time by 30 minutes a week, and there you go).

Many years ago, I wrote an article on this very subject for MR, All You Need to Know in Four Square Feet. I also wrote a book on the subject that could serve as a road map. I caution you against falling into the avoidance behavior trap of spending much time on design specifics. At this junction, the design format doesn’t matter other than keeping it very simple. The key point is to get something simple up on the wall and start thrashing around. Will it look like a crude soap carving? Probably. First efforts generally do. There will be mistakes, likely many. It’s out of those mistakes and slogging in the mud that the foundation of skills you’ll need down the road will be forged.

That day you’re looking forward to will arrive, the day you can FINALLY have that dream layout, of this I’m sure. Prepare for it now so you can make the most of it.