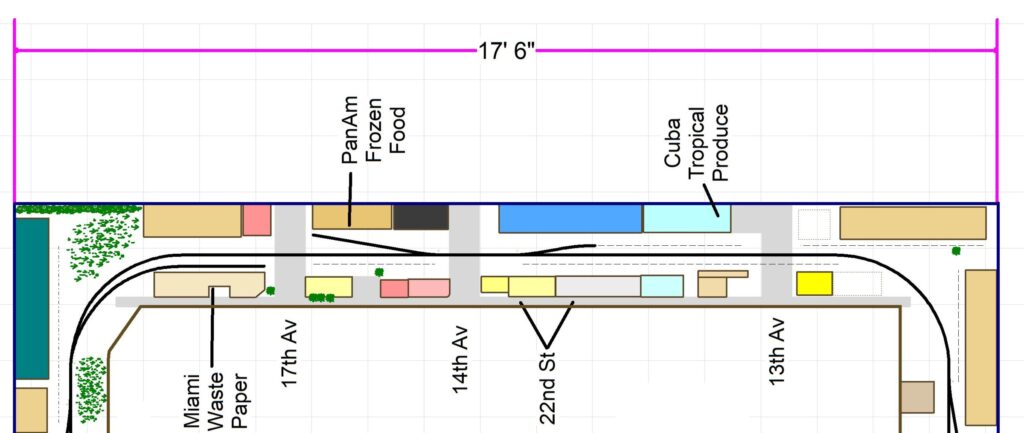

OMNI Transload in Miami’s Commerce Park Industrial zone next to the airport (several hundred yards west of runway 8R). Although it’s one structure, it’s broken down into individual spaces, each leased to a different tenant. In effect, each of those cars serves a different customer. (Thanks to “Mr. Miami”, Tolga Erbora for bringing this operation to my attention.)

Yesterday is gone. The wonder of the 1950s is now seven decades in the past. Let’s shed one last tear, stop staring in the rearview mirror, look at the road in front of us, and open our eyes to the amazing modeling opportunities modern railroading is presenting to us. From a design standpoint, we are decades overdue in terms of taking the time-worn, horrid, bowls of spaghetti of the past and putting them where they belong, in the memory book.

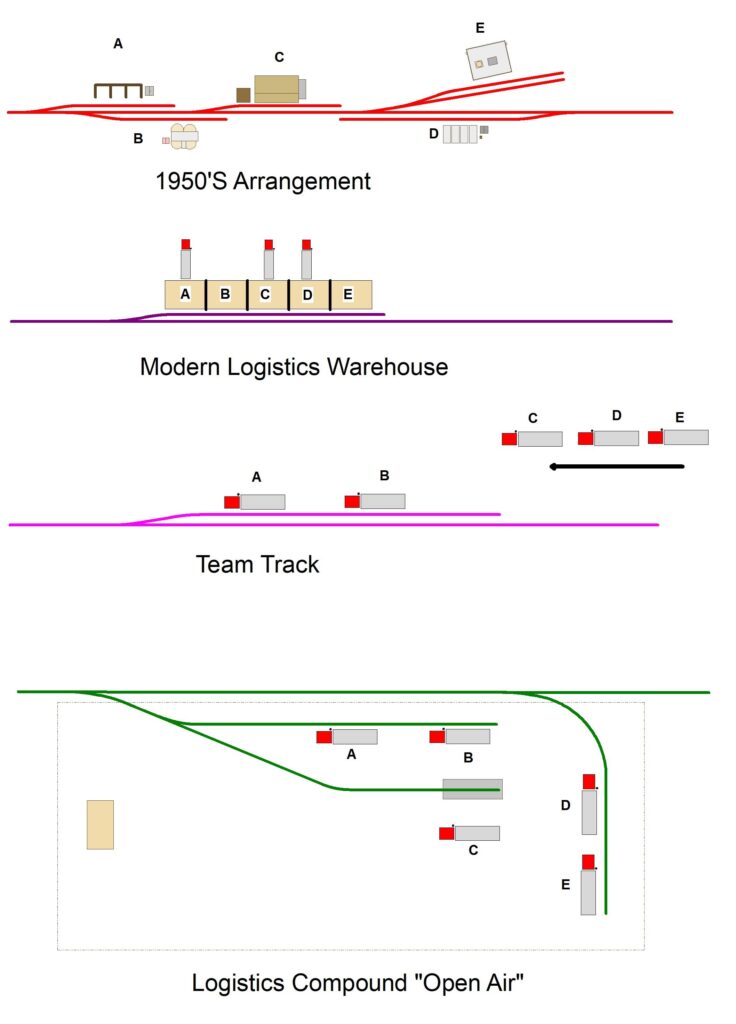

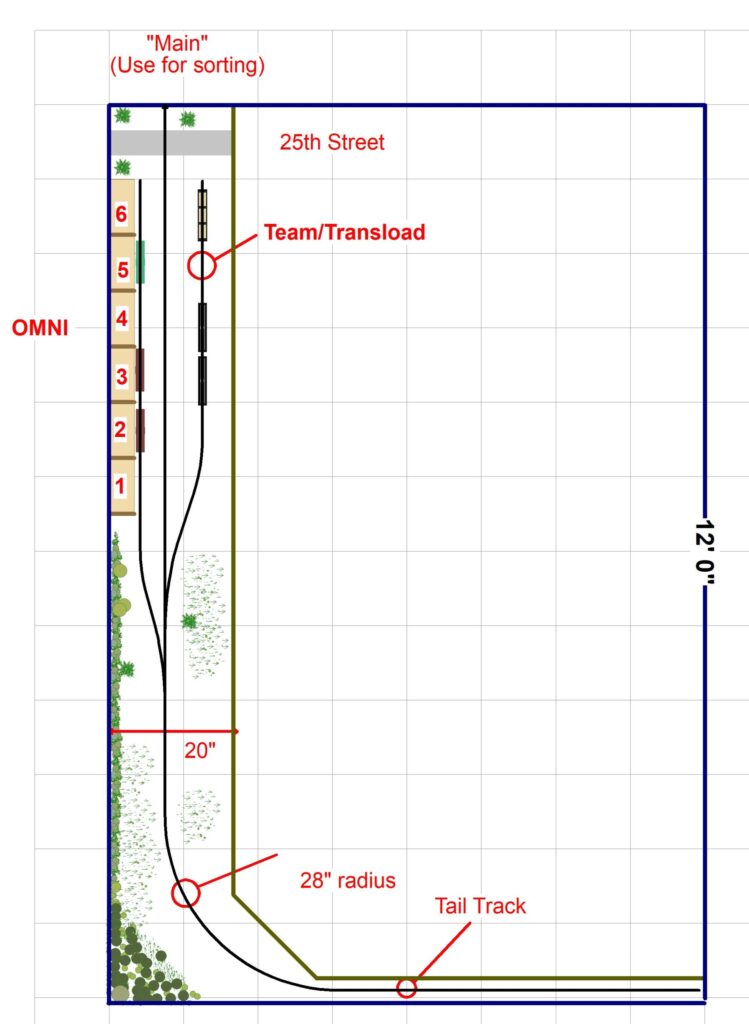

The diagram above shows the evolution of how railroads serve smaller customers. In earlier eras, small customers usually had their own spur. They now lease space in a logistics warehouse or send a truck to a team track to unload their product. From a modeling standpoint the “modern system” is easier to represent and allows you to insert more customers in a smaller amount of space.

If you asked most modelers if the number of rail-served industries has decreased, the overwhelming majority would say yes. That’s partly true but, if you look beneath the surface, a more accurate assessment would be that of change. Without question, the number of industries with their own spur has greatly diminished. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean they’ve stopped getting rail service. In simple terms, what’s happened is that the railroads have said, let’s strike a middle ground here where we both benefit. We’ll still give you rail service. For it to work, we need to trim the infrastructure of those spider web spurs. If you will come to us, or a central location, you can still ship by rail. The nature of these smaller rail-served industries has changed, but the volume hasn’t decreased as much as you might think. And, therein lies an opportunity. Whether it fits for you will depend on how critical the old “building with a spur” in front is to you. What we have now is a system of team tracks, logistics warehouses, logistics compounds, and transload facilities.

Team track spurs often have a fairly generous length. This means they can serve a number of customers at once. Looking at the spur above, it’s clear that cars for two distinct customers are on the lead. On a different day, you’d also see centerbeams of lumber or hoppers of plastic pellets. Note that in modern times they’ve largely gotten away from loading platforms. Trucks just pull up next to the cars.

Here’s an aerial view of OMNI Transload in Commerce Park with an adjacent team track. On this day the team track had two tank cars and two scrap gons.

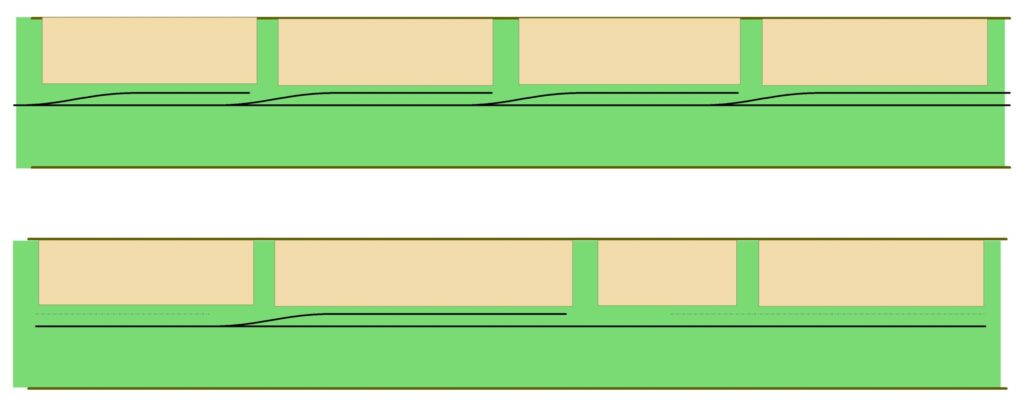

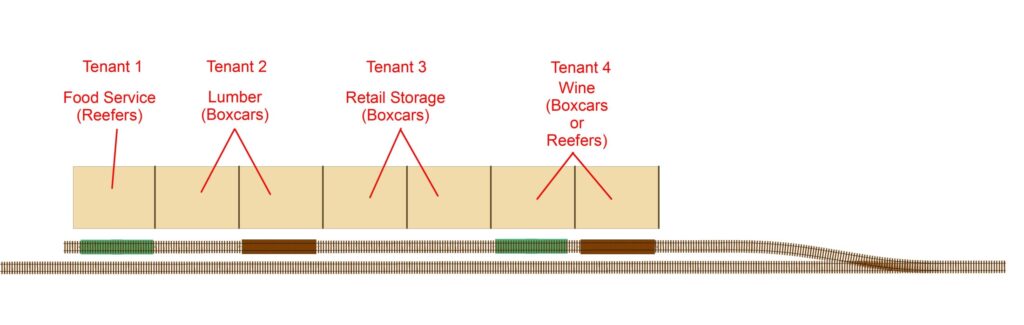

Logistics warehouses are the perfect industry for a model railroad. You get a lot of industries in a small amount of space. Common business renting space in them includes: lumber, frozen food, wine, and dry goods. They offer a lot of operational interest as well since an incoming cut of cars needs to be sorted and spotted in front of the correct customers.

The above design addresses today’s world, a world of efficiency. We only need two turnouts to serve what amounts to eight customers, six at OMNI and two on the team track spur. Operations are challenging, both in real life and for the modeler. Incoming cars need to be sorted correctly before spotting. The prototype would either do this in the yard ahead of time or use the “main” as a sorting track. Then, there’s the issue of the ever-present “problem” customer that GM’s complain about. The one that takes FOREVER to unload their car. Your train comes in with new cars but there’s always that one car in front of the warehouse that hasn’t been unloaded. This means you need to pull it, spot the incoming cars, and then put the problem customer’s car back.

A layout like this checks a lot of boxes:

-Plausible

-Operationally interesting

-Visually interesting

-Inexpensive and easy to build

It offers access to the hobby for anybody ranging from a motivated young student, a busy young person launching their career and starting a family, to a diehard “gray haired” prototype modeler like myself.

Let’s stop bitching about what once was and embrace the fascinating rail world that lies before us.