The Fish Market Seafood Restaurant on East Rail 2

I’ve been hearing a lot lately about carforwarding systems and paperwork. How should the movements be designed? Dice? Computer? Other? What type of paperwork should I use? Prototypical? Car cards? Waybills? Other? Let’s break it down. It depends on the size of your layout and whether the operator is just yourself or a visiting guest.

As far as coming up with an overall scenario for moving the cars, the key issue is layout size. The larger the layout, the more daunting the task is, and the more likely you’ll need some form of computer help. That said, most of my blog readers have small or average size layouts that focus on modest branches or industrial parks. In this case the answer is simple, no dice, no computers…..you generate the movements manually. By far it will give you more plausible scenarios. It’s faster. It’s easier. In most cases you simply aren’t looking at that many cars. Also keep in mind that prototype movements tend to be very repetitive day in and day out. There isn’t much mystery. In Miami you know low-side gons go to FP&T, high side gons go to Miami Iron, LPG tanks go to the only LPG dealer on the line. I don’t even need a list really and doubt the prototype crews does in most cases.

As far as paperwork goes, it depends upon whether you’re operating by yourself or will have guests. As a guest I’ve been handed “prototypical waybills” and spent half the session scratching my head wondering, “what the hell am I looking at? Where on this sheet or card is the information I really need? I don’t care what route the car took or will take two days down the road”. Save the complicated “prototypical” paperwork for when you’re running by yourself. Your guests will appreciate it. A new person is going to be disoriented as it is. They only want (and need) to know two things. When I approach an industry do I pick up any of the cars? When I approach an industry do I drop off any cars and where do I drop them? By default if a car on the layout doesn’t have paperwork that means it stays where it is.

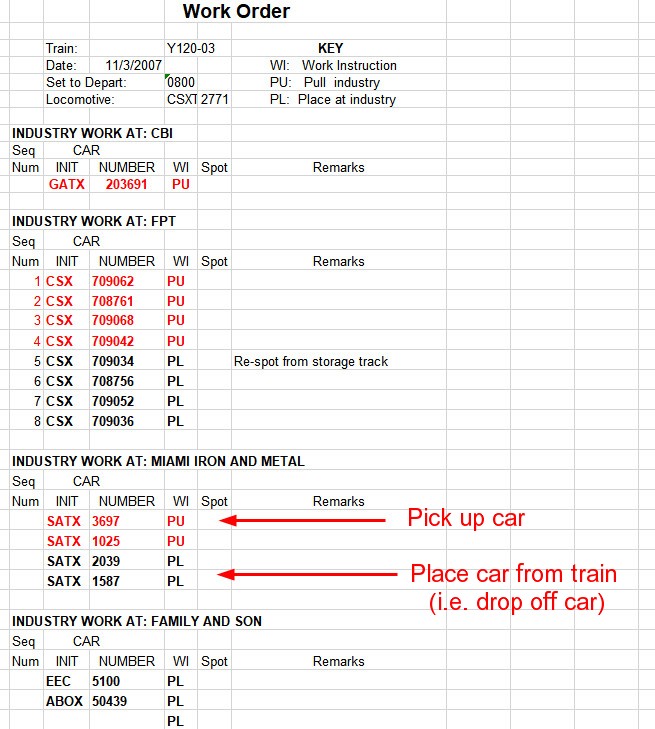

This is the paperwork I use on my layouts and mentioned in my operations book. Three things can happen: you pick up a car, you drop off a car, or if it’s not on the list you do nothing.

Bottom line, if you’re layout is small or of modest size, design the car movements manually. In most situations a super crisp, easy to follow, work order works best for paperwork. You don’t get style points for making things hard to follow and your guests will thank you for it.