Profiling. Demographics, Sociology. Touchy subjects at times depending on the context. Applied with good, or at least benign, intentions however, classifying people into categories can be beneficial both to the individuals being grouped as well as those that are serving them. A major factor in the usefulness of all of this data is how effective we are in choosing our categories. What appears to be a simple task on the surface, often is not. Taking the wrong perspective can result in an entire group being underserved.

As it applies to model railroading, breaking down our hobby demographic by age, scale being modeled, favorite era, etc. is good stuff to know for everybody. One of the more important classifications, and one that often gets just a glancing look, is modeling experience. How many of us are beginners, intermediate modelers, or advanced? You need to know your audience in order to tailor the product or service to their needs. Needs aren’t simply interests but also extend to having the necessary tools to achieve modeling goals. These tools must take into account where somebody is on the learning curve. The most important group is the “beginners” both because of their size as well as the fragile issue of whether they will stay in the hobby. On the surface, this group is served well through the efforts of Model Railroader, train shows, and efforts such as The World’s Greatest Hobby. However, If we dig deeper into what defines a “beginner” we see that we aren’t looking at one homogenous group but actually two. The fact that the model railroading community is benignly ignorant of this reality results in a large segment slipping through the cracks, ignored, and ultimately leaving the hobby, to the detriment of all.

No, not all “beginners” are the same. The term is most commonly used to describe what I’ll call, a “recreational” beginner. This is somebody captivated by trains in general and drawn to the basic appeal of having something in miniature, in motion. They are handicapped by being at the bottom of the learning curve in terms of modeling skills and typically have very little knowledge of (or interest in) the prototype. The absence of any real interest in the prototype or achieving any sense of realism is totally irrelevant. The hobby has done a good job helping the recreational beginner “launch”. They can start by picking up a train set or perhaps following a “how to” tutorial series in Model Railroader. Anything goes and running a 4-6-0 adjacent to an Acela on a 4 x 8 table is totally cool. They have fun and their kids have fun. It’s win, win for everybody including the hobby at large. Some move on to more sophisticated layouts, others stay in the hobby long term and fully enjoy it while staying permanently in the recreational beginner zone. For many more it’s a passing interest which may or may not be picked up again.

The problem, the mass oversight, is that the recreationalist isn’t the only type of “beginner”. There is another silent group which, for lack of a better term, I’ll call the “advanced beginner”. The only attribute they share with their cousins is that they are at the beginning of the modeling skills learning curve. All other similarities end there. (although, even in their own minds they simply call themselves “beginners”).

An advanced beginner is typically very knowledgeable about many aspects of prototype railroading. What they don’t know, they want to know. Realism is important to them. Prototypical accuracy matters to them. Running trains around a loop as a casual rail fan? Not interested. They really aren’t supported by the press because there isn’t an awareness that they even exist. What they want is a model of a railroad but one that can be created using easily learned skills. They want a roadmap that takes them from where they are now down a clearly defined path of ever increasing modeling skills. From a suppliers point of view the advanced beginner, properly supported, is more likely to stay in the hobby long term, purchase ever more expensive products, and ultimately develop into the authors and role models that will move the hobby forward in the decades ahead.

What is their profile? First, they are intelligent. Ages are spread over a tremendous range starting from around age 12 (Yes, it’s frightening but there are some really knowledgeable teenagers out there! Shouldn’t they be studying geometry and not diesel spotting guides?) going well into the retirement years. If I had to pick the most common age I’d say it skews slightly younger in the thirty to early forty year old range. Prototype interests vary but there is a slight skewing towards the more modern time periods.

Sadly, many advanced beginners feel like outsiders, not sure where to begin or how to develop their model railroading passions in modeling form. “How to” series in the press are rarely geared towards them (David Barrow’s series in MR being an exception). They view more established modelers as clickish but are too polite to say as much.

In the eyes of the advanced beginner, pursuing the hobby can be a lonely and often frustrating experience. They want a “model of a railroad”, don’t yet have the skills to create what they have in their mind, and have limited guidance as to how to bridge the gap. On the surface, you’d think being in the age of unlimited information would be the Holy Grail. Unfortunately, lots of information is not the same as lots of quality information. Separating the wheat from the chaff just adds another level of frustration.

If you find yourself in the advanced beginner demographic, here are a few thoughts:

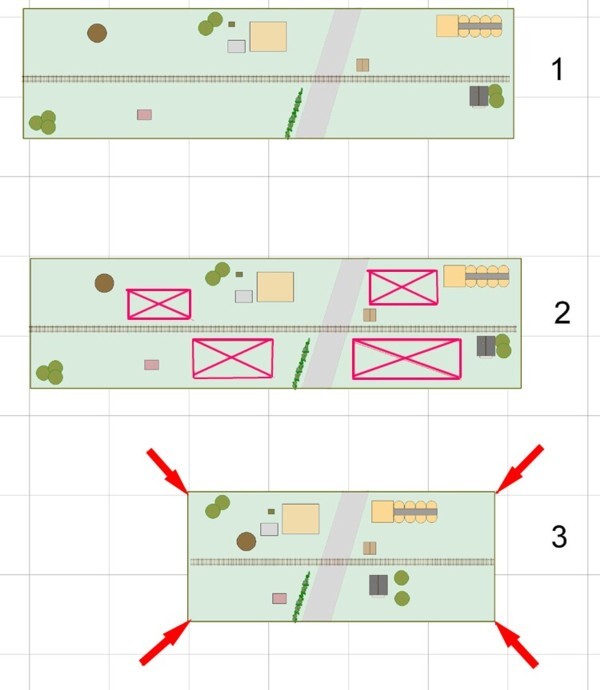

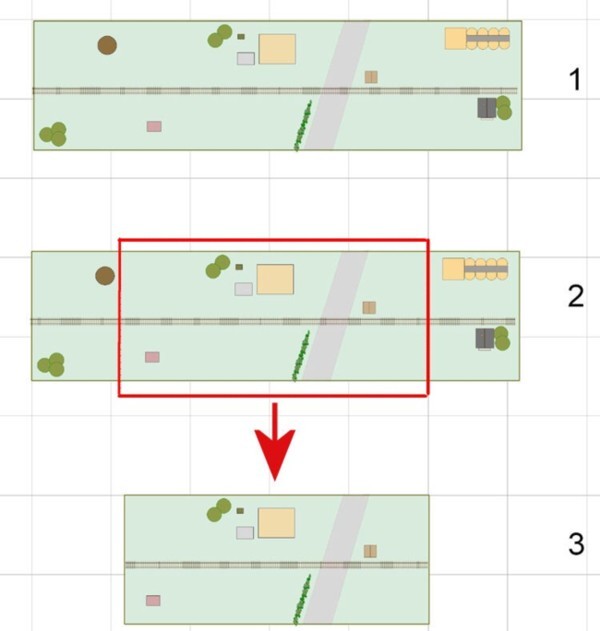

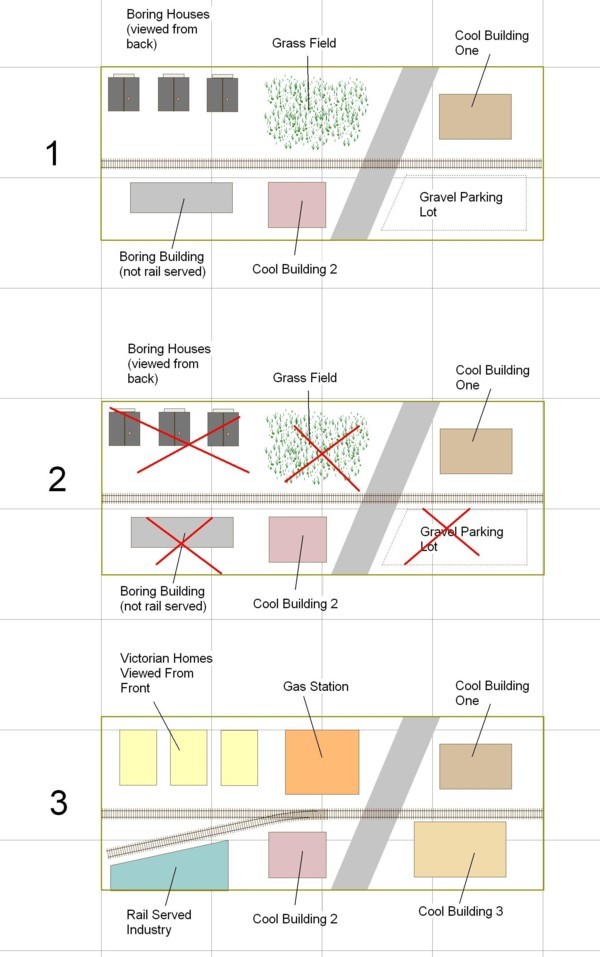

Rather than wringing your hands endlessly worrying about the perfect design, reframe your orientation towards that of breaking the log jam of stagnation and set a basic goal of skills development. Set a target date of building something, anything, and keep it small and manageable. Don’t worry about “perfection”, worry about action. There will be time enough to adjust the tiller as you go.

The nature of model railroading is such that most of the steps are repetitive in nature. If you can successfully build a ten square foot switching layout, transitioning to a half basement model railroad is fairly easy. You just repeat the same steps more often.

Begin your starter layout skills progression by focusing on a three key areas:

- Use Micro Engineering track and paint it with Rustoleum Dark Brown Camo. paint

- Use natural ballast such as that by Arizona Rock and mineral. A good salt and pepper blend is CSX 138-2 secured with dilute matte medium

- For grass use Heki grass mats (#1576) if you’re on a budget. If you have more discretionary income pick up a Noch GrasMaster and learn to lay static grass.

There is a ton of layout design information out there, some good, a lot of it not so good. One of the better sources of consistently reliable, vetted, design information is Kalmbach’s annual periodical Model Railroad Planning. Pick up as many back issues as possible and study them.

Branding yourself as a “lone wolf” is fine but doing so will make the journey much longer and tougher. Ultimately, the path to skills development is paved by creating alliances with skilled modelers that are willing to mentor you. If you’re willing to put yourself out there a little, they aren’t that hard to find. All a mentor will really wants in return is a sincere effort on your part to implement the suggestions.

Finding mentors involves mixing in the circles and networks where you’re most likely to find the more skilled modelers. This can be one of the most daunting, anxiety inducing obstacles. I’m sure from the outside, as with anything social, things can appear quite clickish. This if often more perception than reality. As with other aspects of life, those at the top of their fields are often the most willing to help and those that are the most negative often are those with the least ability.

In order to establish alliances with people that can help you, you need to get out of the house. In my experience clubs are a very mixed bag and not always the best option. As a starting point, I suggest attending some of the prototype modelers meets. Hang out in the model room and ask people what techniques they used. Initiate conversations. Don’t eat meals alone. Three meets that are particularly friendly are in Cocoa Beach, Valley Forge, and Fredericksburg, VA. (not that the other meets aren’t friendly, I just haven’t been).

Forums: These can be a tremendous time sink and the information you receive isn’t vetted. Anybody can say anything, and if communicated with an air of authority, give the impression the information is accurate. Often it is not.

Join the Operations Industrial SIG and attend a few of the operation events. Not every session will be fun but the environment is positive and you’ll be exposed to some high quality modelers in a social setting that lends itself to keeping in touch down the road.

Finally, if you’re looking for a starting point for a skills launch here are two previous blogs that might be of help: