The “new” LAJ layout room, renovated into a Mid-Century Modern (MCM) interior design style. Mid-century modern elements are the bullet planter and faux succulent (from Hip Haven), Z chair (Wayfair), painting (Bed, Bath, and Beyond), and lamp (MCM Gal).

A better title tag for today’s post would be “renovated” layout room. There is no new room per se and certainly no new layout. Although only indirectly related to modeling, my efforts in the past six weeks have been spent giving the room that contains the LAJ layout a total makeover and repurposing.

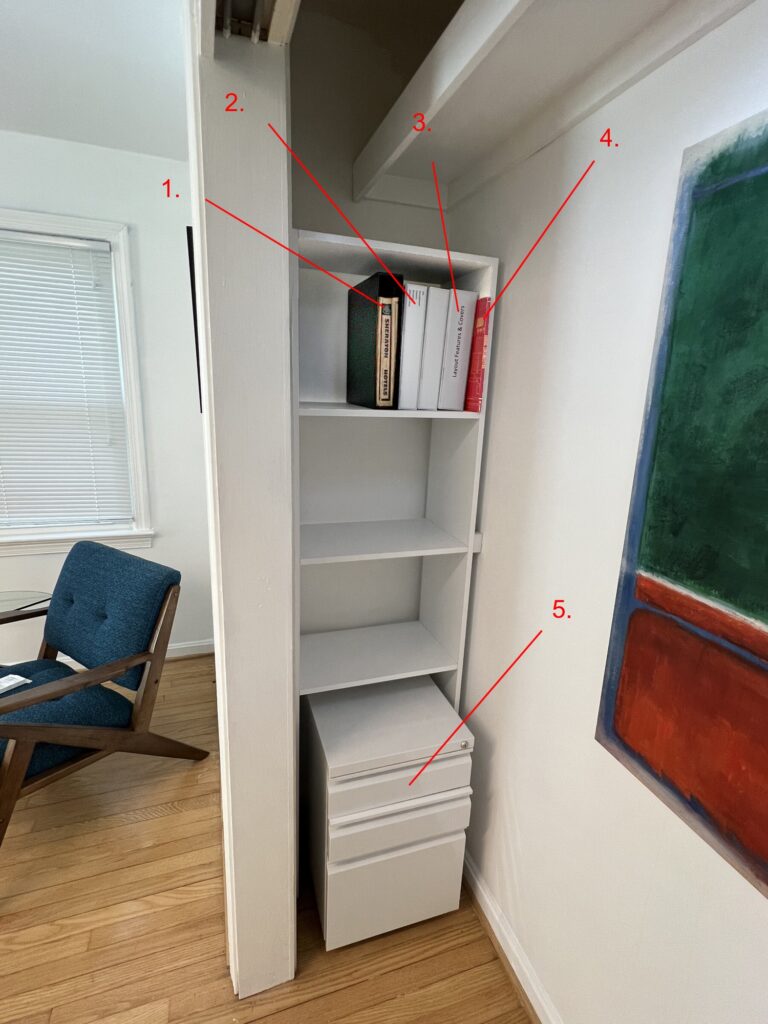

I was getting tired of crawling over the Brooklyn Terminal that was also in the room. I wasn’t happy with the dark closet which contained a ratty old desk. My second computer was in there and I was getting tired of walking from room to room to use each machine. I gutted the space and gave myself a clean slate.

Interior design can fall into the same traps as layout design. “Here’s an empty space, what can I fill it with”? Instead, it’s worth taking a breath, examining the room, and thinking through what its ultimate purpose is. By virtue of its orientation, the LAJ layout room is flooded with magnificent light at the golden sunset hour. I needed a library upstairs. There was my purpose, a library/sun room/space for the LAJ. I hate useless clutter. I hate climbing over crap I don’t need. When I walk up to the window to take in the sunset I don’t want that nagging feeling at my knees of leaning over furniture. I’m a minimalist. If an element doesn’t serve a purpose I don’t include it. I’ve always liked the feeling of walking into a room at an art gallery and being enveloped by the openness. Nothing in the space except art on the walls and perhaps a single bench. The smell of the wood floors. The slight echo of the acoustics. I wanted that.

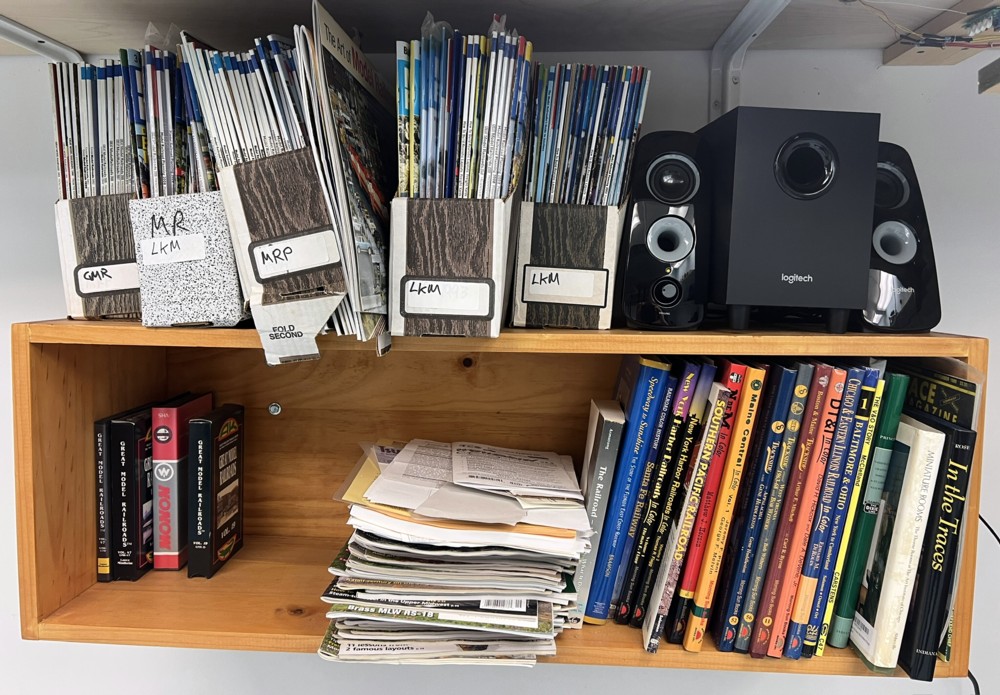

Facing the opposite direction. In the back is the mini-library mentioned in previous blogs. The “Bellet” print on the left was a generous gift from fellow modeler and friend Fred Scheer.

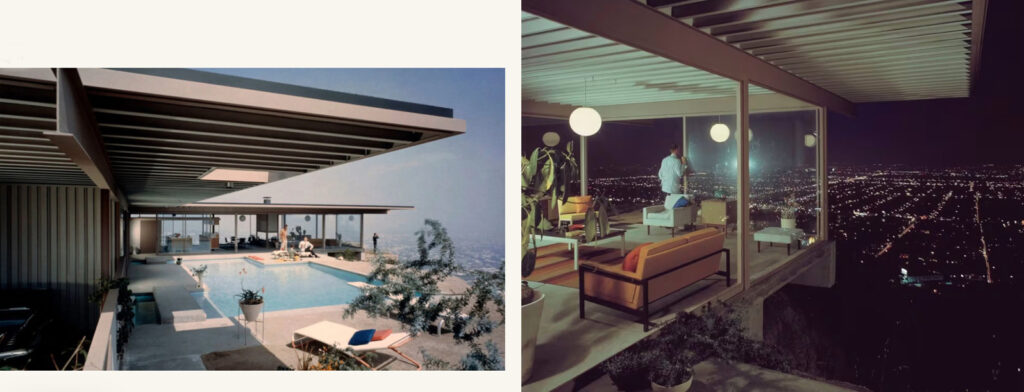

Many years ago my close friend Tom Klimoski introduced me to the mid-century modern design style. The style is synonymous with Los Angeles, especially in the late 1950s and early 1960s. You’ve seen it on the series Mad Men. It’s Stahl House. It’s Palm Springs.

I’ll never own a mid-century home but thought it would be fun to have one room in my house designed in that style.

Here’s a view of how the LAJ fits into the space. I run it several times a week but view it more in terms of “3D wall art”.

Several years after Tom Klimoski introduced me to the MCM scene, another modeler, Fred Scheer brought to my attention a magazine dedicated to the subject, Atomic Ranch. I spent a year or so reading through it to get a better sense of appropriate design ideas.

Stahl House in LA is the personification of MCM design. An argument could be made that it’s the most famous home in the US.