The magic of the internet….It didn’t take long for my blog followers to step up to the plate with more information on the East 38th Street prototype. Thanks to Peter Hegan for letting my know the spur in question is called the Alameda Industrial Lead and pointing me to a YouTube video of some live action.

Model Railroad Blog

Initial Planning

When it comes to planning a layout, a drawing will only take you so far. Fortunately, with a smaller project a lot can be accomplished in 1:1 scale simply by mocking things up full scale with boxes and loose pieces of track. The elements can be re-sized and moved around until you get the look that you want and done so without committing the time and effort to actually building models. The last thing you want is to spend months building something only to find out as things come together that it doesn’t work visually.

The East 38th Street project, by choice, won’t be that large. I’m looking at an L shaped shelf roughly ten feet by four feet. It is all to easy to fall to the temptation to go wider and wider with the shelf width in an effort to fit more in. Once you get beyond eighteen inches, however, you lose that shelf-on-the-wall furniture look. This isn’t a problem for a typical basement style layout but for this project I want to contain the scope. All that said, the space I have is the space I have so design starts with fitting the elements to the fixed shelf dimensions not vice versa.

1. This cluster of structures is the signature element that stamps the layout as being in California and as such will occupy prime real estate. Since they are in the foreground I’ll need to play around with how far I set the track back so that I can make sure it’s visible and that I can reach it.

2,3, and 4. Background structures can be tricky because if they are to tall and shallow the point where the structure meets the wall can be visually jarring. The deeper and shorter the background structure, the less of a problem this is. Since this is a proto freelance project I can move things around. I’ll probably replace building 2 with building 3 and experiment with structure(s) 4. Depending on how much room I have I may include the relatively featureless structure 2 as filler.

5. This block will be compressed greatly and I’ll need to strike a balance between not doing too much cherry picking of interesting structures vs. maintaining the actual feel of the place.

6. The major industry is some type of chemical facility. This will be replaced with something that uses a broader range of car types and spots, probably a bakery.

As the planning comes together, my thoughts will focus on element selection, the depth of the background structures, and photo angles. By being judicious with my industry selection I should easily have enough operational interest to keep me going for an hour or so, more than enough for a secondary switching layout.

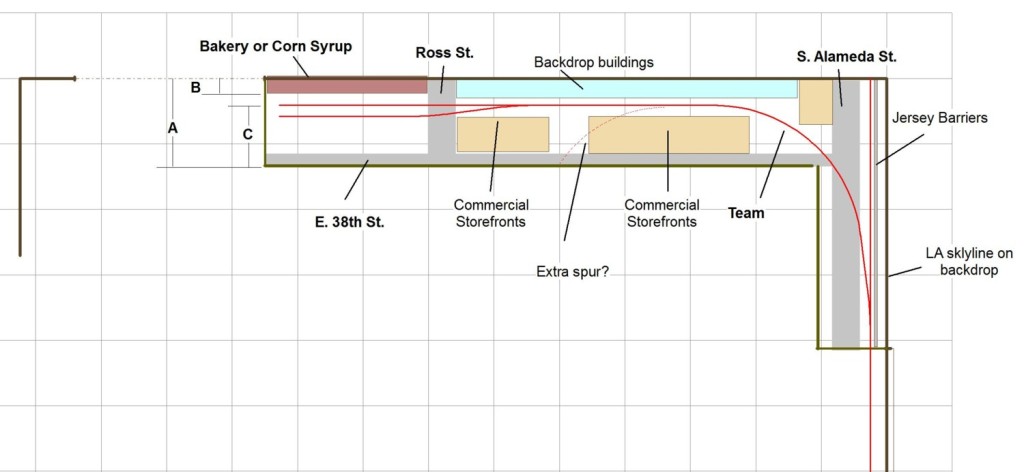

While scale drawings are a necessity, especially for larger layouts, you need to be aware of their limits especially when it comes to how things will look in 3D. A crucial part of this project will be dimensions A,B, and C. I want to avoid mission creep and have a streamlined furniture/shelf look which will require that the shelf width A not get too out of control. Ideally I’d like something in the sixteen to eighteen inch range. The deeper a backdrop structure is, the less jarring the transition at the point it meets the backdrop. It’s a trade off so I’ll play with dimension B using mock ups. The commercial storefronts in the foreground are signature elements but I need to make sure I can see and reach the track over them. To this end distance C, how far the track is from the fascia, will be important.

Introducing East 38th Street

I first became aware of the Los Angeles Junction while in high school and instantly became mesmerized by it. As the decades slipped by the thought of eventually modeling it was always in the back of my mind. I always thought that when the day came, power would be in the form of a CF-7. Oddly, it was a YouTube video of a tandom of two warbonnet emblazoned GP60M’s working a spur that pushed me to “The time is NOW” point. As I spent hours doing my Bing and Google virtual railfanning I wasn’t really finding a scene that inspired me. One afternoon I happened to drift a few blocks away to a neighboring UP spur and found my inspiration at the intersection of East 38th Street and South Alameda Street in Vernon, CA. The layout will be relatively small L shaped shelf project with just a few turnouts. As with my old East Rail layout I’ll use the prototype as something to draw ideas from without following it exactly.

Just modeling the LAJ alone wouldn’t be justification enough to start the project. I want it to be a platform to learn new skills, try new ideas, and apply previously used techniques more effectively. Some things I’d like to experiment with are:

- Battery power

- Powdered glue for ballast and soil adhesive

- Air eraser for weathering and fading

- Photos instead of paint for roads and pavement

- Printing on vinyl instead of paper

- Still lighter bench work

- More realistic dead grass

- More realistic vegetation

- A structure core material that is more stable than .060″ styrene

Room preparation is well underway. I’ll keep you posted. (The Downtown Spur layout is alive and well with no plans for dismantling).

Welcome to the New Look!

It’s hard to believe that it’s been over five years since I first set up the Lancemindheim.com site. Done initially simply as a creative outlet, I’ve been surprised at the volume of traffic that has built up. Tracking the page landings with Google Analytics I’ve also been surprised which pages garnered the most attention. The blog page exceeded that of any other page by a factor of five.

Originally the site was built with an old Microsoft web builder called Front Page. Front page served me well but it has been sunset by all of the hosting companies and it’s capabilities were limited. One common frustration among my blog readers was that the old format wasn’t really searchable. By switching the site over to the Word Press platform that issue has been addressed. In addition it was becoming apparent on my end that the site had become quite bloated and needed some updating and streamlining.

In the months ahead I’ll be transferring content over from the old site to the “Help” and “Blog” pages and ask for your patience as I work on this time consuming task. I also plan to add a tab for RSS subscriptions, another common request among readers.

Reality Based Layout Design

Reality based layout design? By that I mean let’s design for what our lifestyles are ‘actually’ like not what we hope or think they will be. For any of us that have even a passing interest in operations, the driving factor in layout design comes down to the length of an operating session. How much layout do we need to give us the operating session we want? Given that the session length is the what pushes everything on the design front, we need to get a solid grip on it. How long is our session likely to last? My experience has been that most people will have sessions that are far shorter than they expect but also run more frequently (which is a good thing). It’s also critical that you get a realistic handle on whether you will be operating alone or be in a situation where you frequently have guest operators. You’ll quickly find that it is a lot easier to grab a throttle on a whim and have a short solo session after dinner than it is to round up even a small crew for a ‘formal’ session. That means those solo, short sessions become the norm. That’s a good thing. It means you’re in the game, you’re engaged in the hobby.

Let’s design towards the rule not the exception, the norm not the once every two years. For the majority of us, the reality is that ninety per cent of the time we’ll probably be operating the layout by ourselves. Sure, three hour operating sessions sound good on paper but again, let’s talk real world. In terms of session length we’ll have probably “had enough” after about forty five minutes of running. However, we’ll also likely be ready for a repeat of more of the same sometime in the next day or so. In other words for most of us, three, four, or five operating sessions a week that are anywhere from ten to forty five minutes long will be the norm. Let’s design and build our layouts to that end, not the fantasy world of three hour, multi-operator sessions.

If those solo, forty five minute sessions are the norm, let’s design our layout for that and no more. Include just enough industries to satisfy the likely ‘everyday’ and then use the remaining space for scenery. Maximizing ‘greenery’ square footage should be an overriding factor in layout design, not squeezing in ‘more stuff’. It’s having those ample scenery footprints separating ‘urban zones’ that creates a sense of distance and the needed geographical stamp that tells us where we are. I can’t emphasize it enough. During the design process there should be a constant, almost palpable sense of the green scenery expanses constantly pushing industries off the layout edge and out of the design.

The challenge becomes how do we create a design where fifty or sixty percent of the layout surface area is devoid of structures and still create a realistic operating scenario that lasts forty five minutes to an hour? A simple load for empty swap, operated prototypically, will probably only take about ten or fifteen minutes. That means, we’ll need at least four industries to hit our one hour target. However, switching every industry every session isn’t realistic. The prototype doesn’t do that so we’d actually need more than four. Now we’re up to six or seven. For a typical switching layout that’s just too much “stuff” crowding the landscape. It doesn’t allow enough room for scenery. We’re back to square one meaning a typical looking model railroad as opposed to what we want, a model of a railroad.

There is an easy out. The key is to pick one industry that requires a lot of car spots. Doing so gives you the equivalent of many industries in just a few square feet. Commonly found, highly realistic, real world examples are corn syrup facilities, food service industries, and logistic warehouses. Design in one, high car spot industry, and then you just need two or three other industries and you’re good to go. Also, remember that carriers often use any section of a spur next to a parking lot to serve as a team track and that gives you yet another industry. If our one high car spot, anchor industry by itself will give us our target operating session length, that takes the pressure out of the design process. Now we have the luxury of just needing two or three one spot industries to provide variety.

In the above design, if operated prototypically, the corn syrup facility alone would probably take ninety minutes to switch. (Reference Jim Lincolns article on the subject in Model Railroad Planning 2010). That single design decision, the decision of industry selection, is the home run we need. By choosing that particular facility, the op. session length goal has been met before we even start, the rest is gravy. The above plan would be inexpensive, easy to build, and operationally satisfying. It’s attainable to anybody from young student to somebody in a retirement community. The essence of a successful design isn’t about shoehorning in ever increasing piles of crap that won’t ever be utilized. It’s about coming up with a balanced creation where every element has a purpose that, when combined, results in a layout that fits our real life circumstances.