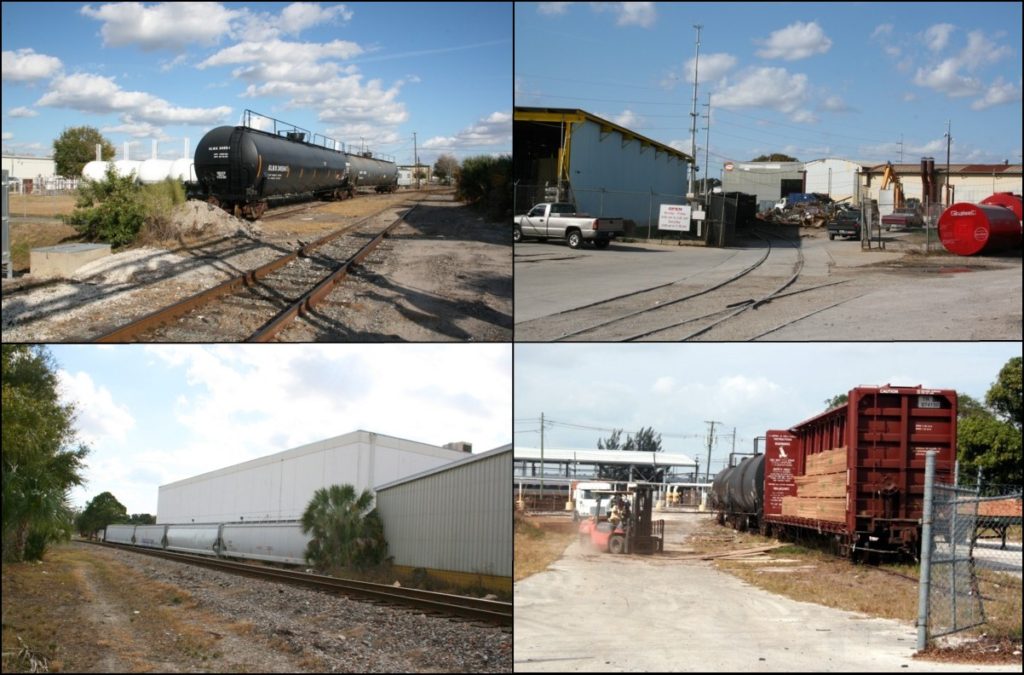

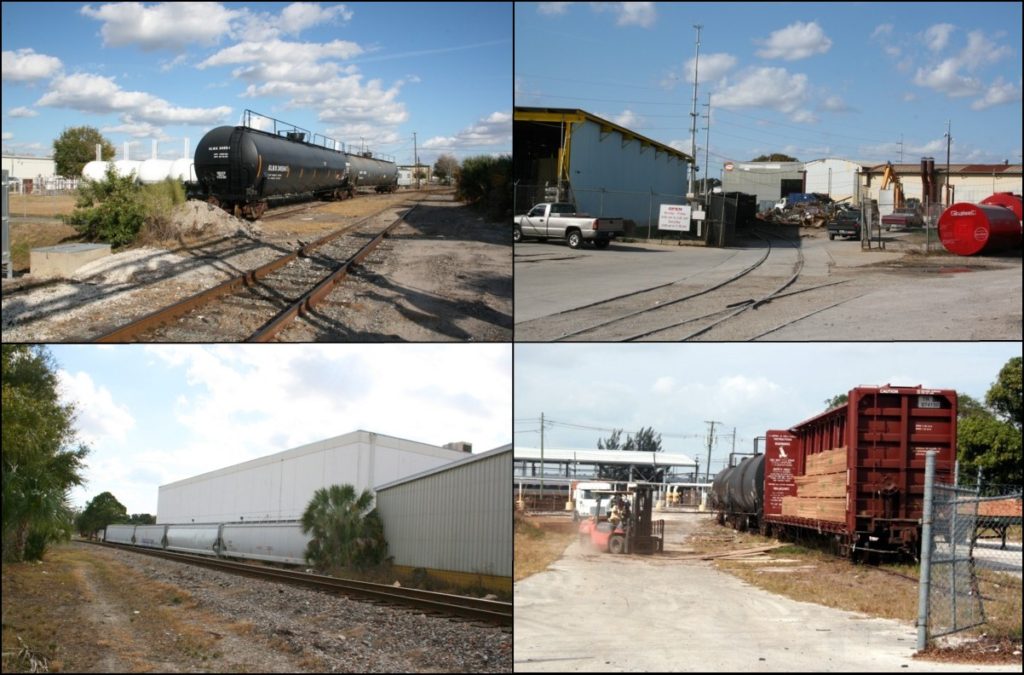

Realism is enhanced when we model industry types that are found with the most frequency. Clockwise from upper left: LPG, scrap metal, team, plastics or warehouse.

Over time, our brain subconsciously registers the most commonly found rail side features whether it be through photos or personal railfanning experience. It expects to see certain elements in certain frequencies. When we look at our layouts, if the eye doesn’t see what it expects to see, subconsciously something seems off and it can be difficult to pinpoint why. The “off” part is typically not picking representative industries, placing our structures too closely together, or not painting them the most commonly found colors.

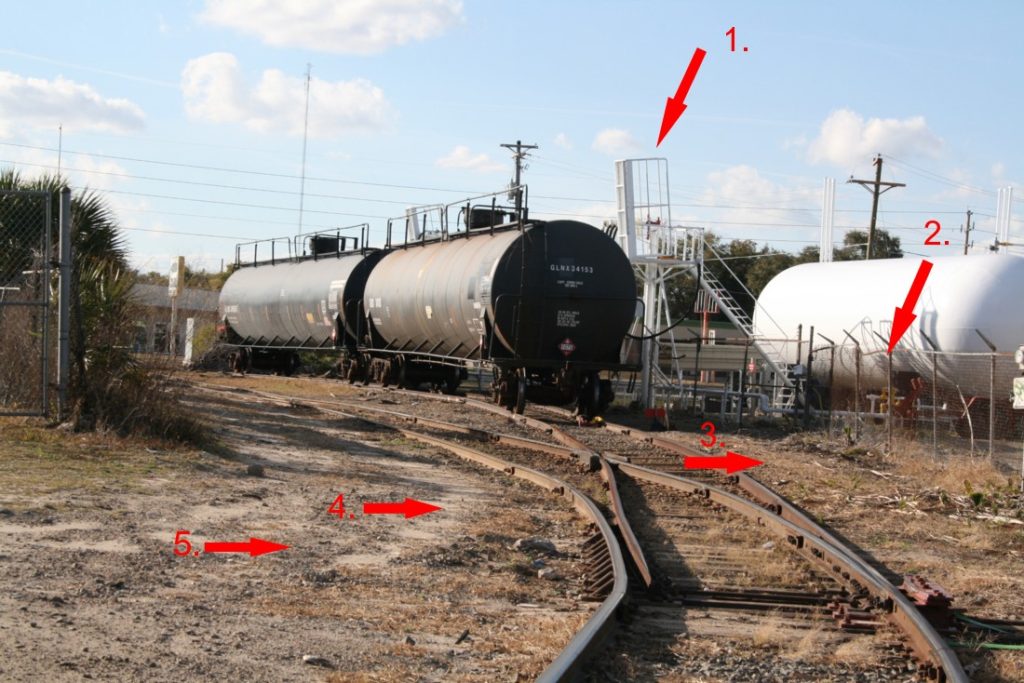

There are exceptions to everything but there are specific industries that are almost always found in any rail served environment. Particularly if you are freelancing or proto-freelancing the more we can stick to the norm in our industry selection the better the layout will look. To an extent, this is era specific. If you model the steam to diesel transition era, Sanborn maps will show that almost every town had: a timber unloading ramp serving as a team track, a lumber dealer, and a fuel (coal or heating oil) dealer. In the modern era, you certainly have the leviathan industries such as coal, chemicals, auto rack unloading, grain elevators, and ports but these can be hard to model given our space limitations. As you move into the urban areas though, modern era industries include a heavy dose of: LPG facilities, scrap metal, warehouses or plastics facilities, and the timeless team track.

When designing your layout, the vast majority of your industries should be those that are most commonly found in the real world.

Finally, a note on color. As you look at the photos note the preponderance of white and grays. More than half of your structures should be colored accordingly. Note the amount of dead vegetation. A heavy dose of your rail side vegetation should be beige, not green.

Model the ordinary, not the extraordinary, that’s the key to realism.