A pair of boxcars sit in front of A-1 Farmers Choice on the switchback segment of my Downtown Spur layout.

A successful model railroad design is one that provides a platform for several hours a week of relaxing hobby time…recreational time…..fun time. It doesn’t really matter how those minutes or hours are spent. If there is some degree of completion on a layout, module, or diorama and you find yourself working on it somewhat consistently, congratulations, you’ve come up with a successful plan. A two hundred turnout, dog’s breakfast of a layout plan isn’t successful if it never gets so much as started, let alone built.

More than half of the people I know never reach the point of having even a basic operational test track tacked down, often after decades of design noodling. I could (but won’t) write an entire book on what I suspect the underlying psychology for this is. However, if I take a look at that pool of bystanders, and separate out the smaller subset of those that truly want to be engaged, I keep coming back to one central cause for the logjam. It’s overreaching with the design. There is a disconnect. On one hand there is what they “think” is the absolute bare minimum scope they need in order to motivate them to build something/anything. On the other side of balance is their actual level of time/energy/focus level. The problem is the two don’t match. In other words, “I need X to be happy but I only have .5x in the tank”.

The secret to design success isn’t finding a way to squeeze more in but rather understanding how to be satisfied with less. Less doesn’t mean less sophisticated and it doesn’t mean “settling”. A starting point of that process is having the self-awareness to truly understand what aspects of the hobby you enjoy most.

As an example let’s look at a typical modeler. They likely enjoy structure building, rolling stock tuning/weathering, and running trains by themselves in half hour bursts. They have other obligations and interests such as family, home maintenance, jobs, etc. Matching those real world time/energy constraints with typical modeling interests and get at least some railroad up and going is very attainable… if you have a good design. If you can come up with that plan, then you have the foundation for those several hours of relaxation and satisfying hobby time. It doesn’t take many turnouts or that much square footage either.

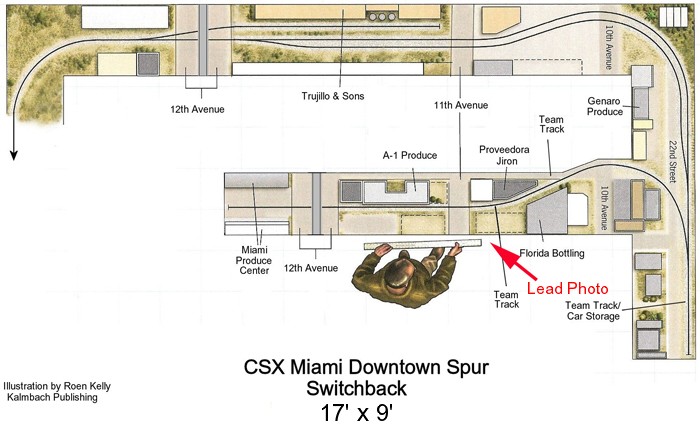

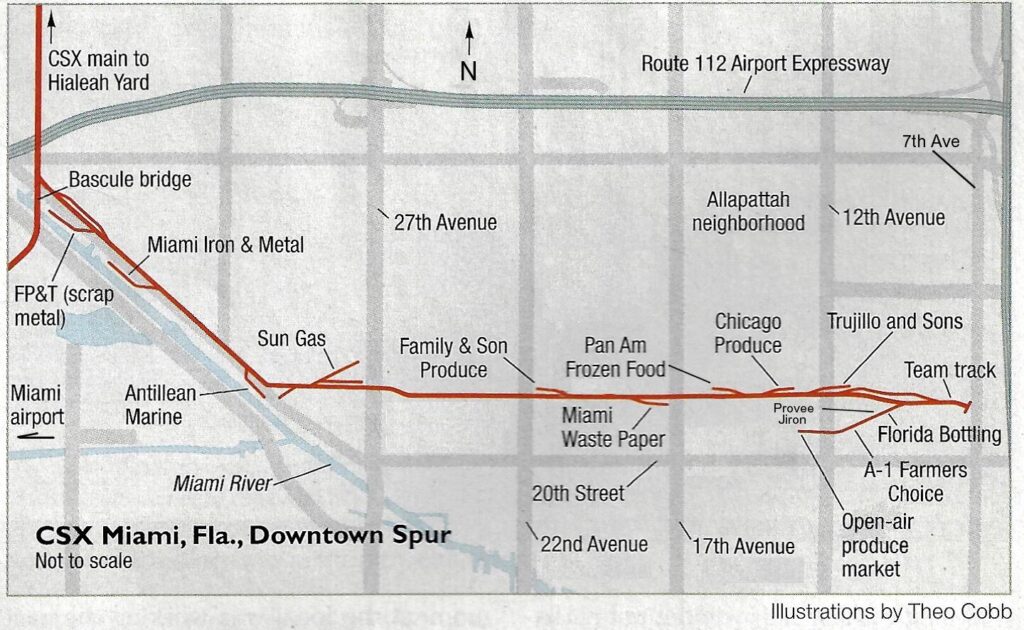

Shown above is an example. The prototype is the switchback at the end of Miami’s Downtown Spur. It’s only half a mile long and doesn’t have a single siding. Even so there are four industries along the route plus three additional locations that are used for team track loading. That gives you seven places to spot cars. There is a runaround siding just before the switchback that allows for the required moves needed to switch the lead. You could have the bench work down in one or two weekends. Throw down three or four Peco turnouts and you have everything you need. At that point you could spend years of hobby time building the structures and rolling stock. Solo operating sessions would easily run over a half hour, but probably more. If you wanted to further simplify things, you could eliminate Trujillo and Sons (top of plan), narrow the bench work and just treat the siding as staging. As basic as this is, I’d guess it would take the average hobbyist five years or so to “finish”. Five years of fun, of satisfying leisure time, isn’t “settling”. So, do you want to spend the next five years building models and running some trains as you sip your favorite drink and listen to music, or do you want to spend it on ebay, forums, and social media? None of us are guaranteed a tomorrow so some food for thought.

Need Help Designing Your Layout? Check out my model railroad design services HERE.