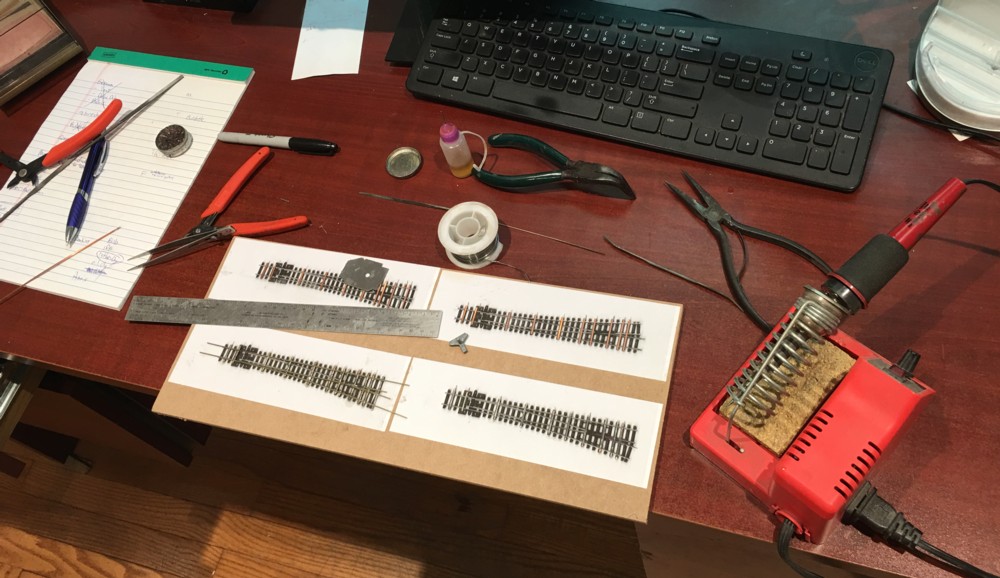

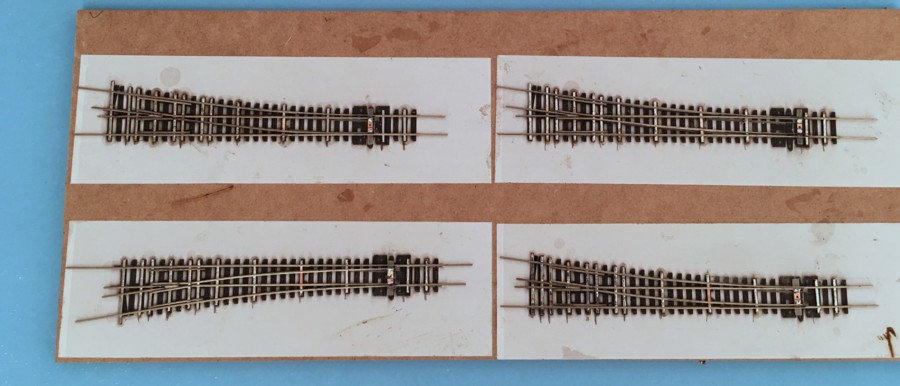

In a way it’s much easier to scratch build turnouts in groups. You tend to get into a groove after the first one, and progress is much quicker. The four I need for the yard are now done (code 40, number 6’s). I did an article on the subject in the November 2011 issue of Model Railroader.