After the initial false start, I finally wrapped up the floating bench work construction. Often, the impact of our layout environment rarely reaches the level of conscious awareness. However, a clean execution of the bench work and room environment sets a tone that enhances the entire experience of interacting with a layout. It makes us want to be in the room and the effort is never wasted.

Model Railroad Blog

Putting the Pieces Together

In the July issue of Model Railroader, Tony Koester wrote what I’d consider to be one of his best Trains of Thought columns. In the piece he clearly communicates the notion that simply producing a model that is neatly constructed won’t bring you to the finish line if your goal is create a successful scene. I define a successful scene as one that gives you the visceral feeling of being transported to the time and place that evokes the pleasant memories we are trying so hard to capture.

Tony writes: “Modeling railroading, as opposed to basic model railroading, is indeed an art form. Just building exquisite models won’t come close to achieving a sense of a railroad going about its daily toil. How they’re situated, which models we choose to include, how well they’re weathered, whether they complement the function and appearance of the railroad – all of those factors and more come into play when our goal is model railroading.“

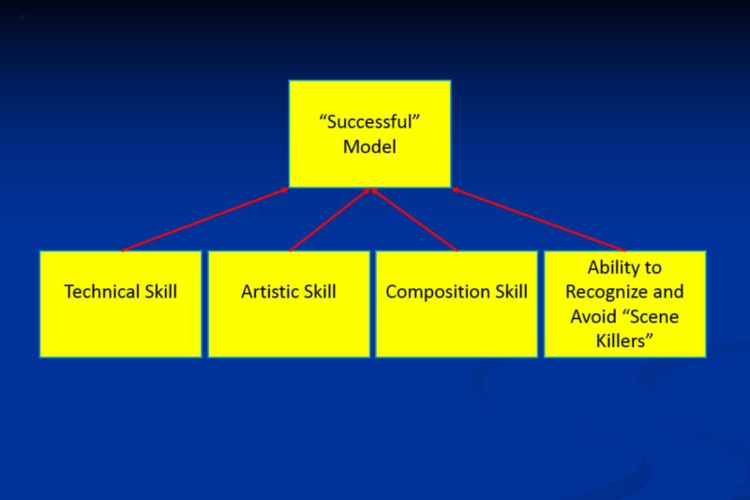

We can’t reach our goal of achieving a successful model, however, if we don’t have a crystal clear awareness of the factors that must come together to reach that end. The graphic above illustrates the four skills that must be mastered and combined in order to achieve “success”.

Technical skill refers to how well we handle basic assembly tasks. These include clean joints, surfaces free of adhesives, neat lines, and smoothly applied paint. As Tony points out, you can have a model that is technically correct but doesn’t still look very realistic.

Artistic skill has to do with color selection and application as well as material selection. In other words, getting the right color, in the right place, in the right pattern. If you want to see this in practice take a walk through the images on The Rustbucket forum. Color selection alone isn’t enough. We also need to select the correct textures. Examples include static grass instead of ground foam, high quality ballast, etc.

Composition has to do with the elements we select for our scenes and of even more importance, the space between them. Modelers constantly struggle with the spacing issue, often place elements too close together, and detract from would otherwise be a successful result. Composition also has to do with selecting accurate cross sections. That mean posts, mullions, hand rails etc. that are not overly thick.

Finally, a modeler needs to cultivate an eye towards recognizing scene killers and avoid placing them in said scene. Frequent offenders are cheaply made chain link fences, power lines, cheap vehicles, clunky figures, unrealistic signs/billboards, etc.

None of this comes overnight and the first step is an awareness that the elements exist and their importance in getting you to where you want to go.

Floating Shelf Fascia

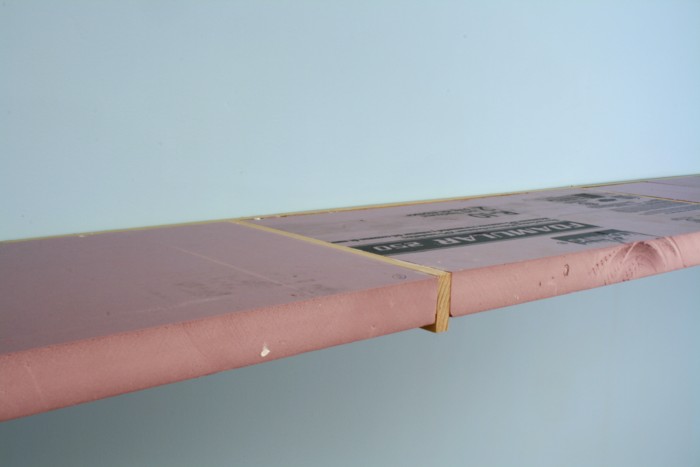

For the fascia I needed something that was both stiff and hard but also relatively light. Styrene is too dimensionally unstable, traditional molding or MDF was too heavy. A trip through The Home Depots molding aisle turned up what I needed, 2 1/2 inch by 1/4 inch thick “lattice”. After carefully cutting it to length I ran a bead of DAP adhesive caulk along the face of the foam and wood glue along the face of the outriggers. I then tacked the lattice to the face of the outriggers using #17 by 1 inch wire nails (brads). Things are looking good at this point as the bench work is very solid, even when pressure is applied to the edge and I’ve achieved the clean look I was after.

Floating Bench Work

Occam’s Law can be summed up with the adage K.I.S.S. In other words, the best solution is typically the simplest. Simple doesn’t mean easy to design. Often the opposite is the case. It takes a fair amount of thought to come up with the cleanest approach. Whenever I find myself using the proverbial duct tape, baling wire, and a prayer to make a concept work, I know I’m on the wrong track. Such was the case with the threaded rod idea for my floating bench work. Pride of ownership can overcome all of us but I ultimately had to resign myself to the fact that the idea simply would not work. Even with stiffening tubes the rods were too bouncy. The Hillman anchors, while probably great for short levers such as towel racks, couldn’t handle the torque and were becoming slightly unseated from the wall. Finally, extruded foam slabs have a slight warp to them. Without some sort of frame to secure the slab to, there is no way to overcome the warping. Simply setting the foam on the rods wouldn’t work.

Back to the drawing board. The challenge of floating bench work for a model railroad is the deeper shelf depth which results in a longer lever. To over come this you need: a light frame, a very strong anchor to the wall, and you need to eliminate as much weight as possible from the end of the outriggers (levers). The design above solves all these problems and meets my goal of a clean look while at the same time being very solid. For the plate against the wall I used poplar as it is harder. I used lag bolts and large 1 1/4 washers to securely fasten it to the wall studs. The outriggers are select pine attached to the poplar with relatively long, three inch drywall screws. I used a Forstner bit to remove material from the end of the outrigger to lighten it up. There is no facing frame on the end of the outriggers as that would have added too much weight.

The outriggers are on 32 inch centers. After the frame was in place I inserted two inch thick extruded foam slabs between the outriggers. I haven’t decided on a fascia material yet but need to find something relatively light.

Powdered Glue

The initial test on a six inch piece of test track of powdered glue as ballast adhesive showed promise. I’ve since moved to using it full force on a large N scale project in my shop. Again, success. I find it is not only easier to use than traditional liquid adhesive but it’s also easier to get better results. Better being defined as no floating ballast, no craters, and no mini trenches. I haven’t yet dialed in the best ratio of glue to ballast so can only say the amount of powdered glue needed is “not much”. At present I’m putting two, 10 oz. bags of ballast in a bucket with only 1.5 oz of glue and it holds very well (that comes to 1:13). One caveat is that the glue is very sensitive to moisture in the air and when exposed to it will start to dry. I’m noticing that after mixing the ballast and glue in a bucket and leaving it over night there was some drying. That being the case I suggest storing your excess in a container with an airtight lid. If over time I find I didn’t use quite enough powder the ballast would be knit together enough that a quick follow up with dilute matte medium would be easy to do as insurance. Finally, there is warning label on the glue container letting you know the powder is a lung irritant and not good to breath. That is certainly the case so wear your respirator when working with the stuff.