I added a section of photo wallpaper sample images for people to download in the How To section.

Model Railroad Blog

Downtown Spur Video

MR Video Plus just uploaded their video of The Downtown Spur. You can view it HERE.

Preparing For The Day You Have A Layout

Wrote a post on preparing for the day you finally have a layout. You can read it on my business site HERE.

Or….cut and paste: http://shelflayouts.com/2016/03/preparing-for-the-day-you-have-a-layout/

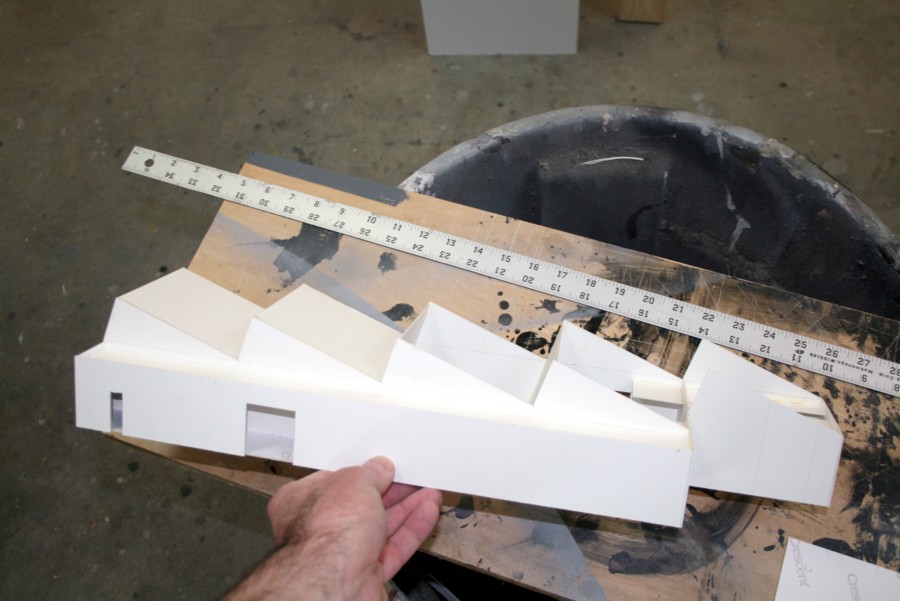

Illustration Board Cores

The core for Modern Pattern and Foundry was made from illustration board.

Having depleted my supply of large styrene sheet material, I decided to try something different for my structure cores, illustration board. An email to a friend that has been using the board for years confirmed that it is viable and doesn’t warp over time as long as you brace it sufficiently. A quick trip to Michaels and I was good to go. It’s easy to cut with a utility knife. For adhesive I use wood glue with the occasional spot of CA gel. As further insurance against warping, I sprayed the finished core with shellac.

Chain Link Fencing

It’s a common modeling problem. We’re trying to model something we see on the prototype and the only part available is grossly out of scale. The problem compounds if the part in question is something we see every day. Do we omit the part? Do we include the crude “soap carving” so we can say we took a stab at what is actually there?

Experienced modelers often offer the sage advice “No detail is better than a bad detail” something we should think long and hard about. For the sake of clarification, I’m going to call a “bad” detail as one that is overly thick in cross-section.

The starting point of the discussion always has to begin with knowing how thick the element in question actually is. Next, we have to gain an inherent awareness of how large a scale inch is on the scale we model. I’ll save you the trouble of looking a few things up…

A scale inch is: .011″ in HO, .006″ in N, and .021: in O. Worth committing to memory.

All of this brings us to today’s topic, a perpetual thorn in our modeling rears, modeling chain link fencing. Exceptionally fine and delicate in nature, it can be difficult if not impossible to scale down the mesh to scale size. What to do?

Actual chain link fencing has mesh an eighth of inch thick (.001 in HO), five openings per foot, and dark grayish brown in color.

The first step is to recognize we have a problem. We need to recognize that most commercial representations of chain link fence aren’t even close and trying to make them work is so visually jarring that you would be far better off simply omitting the detail. The second step is gaining an understanding of the dimensions involved. In other words, measure a fence. The spacing of an actual fence mesh works out to five openings per foot. The mesh itself is an eight of an inch in diameter, which scales down to a mere one thousandth of an inch in HO. Holy crap! Finally, color is paramount and fence mesh is not silver as many modeler’s frequently use, it’s a dark brownish gray. Painting an oversize part a bright color accentuates it’s liabilities, painting it a darker dull color disguises or downplays liabilities.

BLMA fencing, Berkshire Junction EZ Line for barbed wire, .020″ fence posts.

In looking at the commercial fencing products on the market, the fencing put out by BLMA is by far the best. BLMA is the best material for commercial fencing though. While the BLMA mesh appears very fine, it’s actually about five thousands of an inch wide. In other words, it scales down to five eights of an inch in width compared to the one eighth of an inch of the prototype. That’s five times oversize. To combat this I put a fair amount of time in knocking the shine and lightness off of it. First is a coating of Dullcote. I follow this with multiple light passes of a dark India ink/alcohol wash applied with an airbrush. In some cases I will also dust on some dark brown chalk also.

Chain link fencing is such a common feature of the landscape, and modeling it effectively so challenging, we need to tread lightly so as not to detract from other areas of our layout we’ve worked so hard to model convincingly.